|

Summary

As soon as he had signed the Munich agreement, Hitler set about conquering the rest of Czechoslovakia. He ordered his army to be ready to invade, and then plotted with the Slovak leaders to riot for independence. Then he bullied the Czechoslovakian President Hacha into asking him to help with the trouble, and sent in his army (15 March 1939).

Chamberlain's reaction was weak - he would not accuse Hitler of breaking the Munich Agreement, and said that Britain could not do anything because the Czechs had invited Hitler in.

The British public, however, reacted with fury. In response, Chamberlain warned Hitler that Britain would fight if it was decided that Germany was trying to dominate the world by force, and the British government guaranteed Poland's independence (30 March 1939).

The American journalist and historians William Shirer believed that Czechoslovakia was the moment that Chamberlain abandoned appeasement. However, the facts show that Chamberlain continued trying to negotiate a settlement with Hitler right up to the end of August.

The Occupation of Czechoslovakia

As soon as the Munich agreement had been signed and German troops were entering the Sudetenland, Hitler was plotting the occupation of Czechoslovakia:

• On 21 October 1938 he ordered that the Wehrmacht ‘must be prepared at all times for … the liquidation of the remainder of Czechoslovakia’.

• The Nazis set about destablising the Czechoslovak state. On 17 October 1938 Goering met with leading Slovakians and arranged with them to campaign for independence; he wrote: ‘A Czech state minus Slovakia is even more completely at our mercy. Air base in Slovakia for operation against the East very important.’

The Munich Agreement laid down that Germany, Britain and France would make a separate treaty guaranteeing Czechoslovakia’s independence. When the British and French governments eventually asked about this until February 1939, Hitler replied that he needed to ‘await first a clarification of the internal development of Czechoslovakia’.

He was waiting for his Slovak allies to create chaos. Slovak separatists were campaigning for independence, and by early March 1939 there was open rioting in Slovak towns. At the same time, separatists in Ruthenia (a small area at the eastern end of Czechoslovakia) started demanding independence.

Hitler seized the moment.

• He sent a military delegation to Bratislava (the capital of Slovakia), which put the Slovak leader, Tiso, on a plane to Berlin; there he was harangued by the Fuhrer and given a declaration of Slovak independence to sign (14 March 1939).

• Next to arrive was Hacha, the Czechoslovakian President (14 March 1939). He was kept waiting until 1:15am next day, and then bullied and harrassed until he fainted; Hitler’s personal doctor brought him round with an injection, whereupon the bullying continued until, at 3:55am, he signed a prepared document asking the German army to ‘place the fate of the Czech people and country in the hands of the Fuhrer’.

Source A

[Hitler] could make it appear – he, who, alone in Europe, had mastered the new technique of bloodless conquest, as the Anschluss and Munich had proved – that the President of Czechoslovakia had actually and formally asked for it.

William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1959).

At 6am on 15 March 1939, German troops poured into Czechoslovakia. The anti-Nazi American journalist and historian William Shirer comments: ‘A long night of German savagery now settled over Prague and the Czech lands’. Slovakia was given independence under German ‘protection’, and Ruthenia was given to Hungary.

First reactions

Chamberlain announced the events to the House of Commons on 15 March 1939. Many MPs were horrified at how weak

his statement was:

• Although he admitted that Hitler, for the first time, had annexed a non-Germanic population, Chamberlain refused to call Hitler’s action ‘a breach of faith’, saying only that is was not in ‘the spirit of Munich’.

• He emphasised that no aggression had taken place, and that the German actions had taken place ‘with the acquiescence of Czechoslovakia’.

• And he finished by reasserting the government’s aim ‘to substitute the method of discussion for the method of force in the settlement of differences’.

The official protest to Germany was even weaker, beginning: ‘His Majesty’s Government has no desire to interfere unnecessarily in a matter with which other governments may be more directly concerned…’

In the rest of Britain, however, there was a violent reaction against Germany.

• In Parliament, the MPs reached ‘a pitch of anger rarely seen’.

• Every newspaper except the Daily Mail condemned Germany.

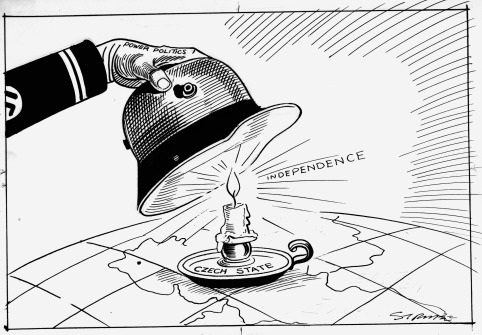

This cartoon, by the British cartoonist Sidney 'George' Strube, appeared in the Daily Express on 16 March 1939.

It shows the attitude of the British public towards Germany.

Faced with this public anger, therefore, on 17 March 1939 Chamberlain gave a speech in Birmingham, in which he said:

Source B

Is this, in effect, a step in the direction of an attempt to dominate the world by force? While I am not prepared to engage this country by new and unspecified commitments under conditions which cannot now be foreseen, yet no greater mistake could be made than to suppose that because it believes war to be a senseless and cruel thing, this nation has so lost its fibre that it will not take part to the utmost of its power in resisting such a challenge if it were ever made.

Chamberlain’s speech in Birmingham, 17 March 1939.

The Results of the Occupation of Czechoslovakia

William Shirer believed that the Birmingham speech marked the end of appeasement:

Source C

This was an abrupt and fateful turning point for Chamberlain and for Britain… The Prime Minister at last saw that Hitler had deceived him.

William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1959).

And the evidence and result of this, Shirer says, is that on 31 March 1939, the British government issued a note saying that: ‘His Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Polish government all support in their power’ if Poland was invaded.

Other historians are not so sure that Chamberlain had had a change of mind:

• Most of the Birmingham speech was justifying appeasement, not abandoning it.

• Even the part of the Birmingham speech ‘warning’ Hitler (Source B) was hedged about with ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’ if you read it.

• On 3 April 1939, when he was challenged about the Guarantee to Poland, Chamberlain said that it pointed ‘not towards war, which wins nothing or settles nothing, cures nothing, ends nothing,’ but that it pointed the way towards: ‘a more wholesome era, when reason will take the place of force’ – which is just appeasement talk, and certainly not confrontation talk.

• Chamberlain did nothing to prepare to defend Poland, and he failed to make an Anglo-Soviet alliance which would have stopped Hitler’s invasion.

• Even in the last days of August 1939, during the Danzig Crisis, Chamberlain was still trying to negotiate with Hitler through the British Ambassador and an intermediary (Birger Dahlerus, a Swedish businessman, who was smuggled in and out of 10 Downing Street).

• On 26 August 1939 Hitler demanded Danzig, but offered Britain a Non-Aggression Pact and a promise that Germany would defend the British Empire; Dahlerus was sent back with a message that ‘England was willing in principle to come to an agreement with Germany’.

|