|

|

This idealistic painting of a German farmer captures Darré''s ideal of Blut und Boden –

an archetypal Bauer farming his plot traditionally, and perfectly, set in a German landscape.

|

THE POWER OF THE LANDSCAPEHistorian Thomas Zeller (2005) argued that lovers of the landscape in 1930s Germany believed that there was a connection between the landscape and the human soul, and that Germany's landscape "embodied the values of a specific community whose characteristics were increasingly coming to be seen as based on race". This was the meaning of Darré’s idea of Blut und Boden, of a Volksgemeinschaft defined by its race and landscape. Some historians have suggested that there was a contradiction between ‘blood’ and ‘soil’ in Nazi thinking. What if a German lived outside Germany? Were they fully German or not? I see no problem; the Nazis simply believed in the supremacy of all things German – the Aryan race was superior to all other races, and the German landscape superior to all other landscapes. One outworking of this, therefore, was that a true German would be a nature-loving soul as part of their commitment to Germany's homeland. Moreover, since another aspect of the Nazis’ ideology was that they saw the acquisition of personal possessions as a 'Jewish' social evil, a true German, therefore, was expected to find fulfilment not in disposable wealth, but in a love of the German landscape and wholesome activities in the countryside. One of the leisure activities organised by the KdF were walking holidays in the mountains for 28 marks a week, or, in winter, skiing holidays in Bavaria. We see this veneration of Germany’s natural landscape also in the films of the time. The widely shown and very successfully propaganda film Hitlerjugend im Bergen ('Hitler Youth in the Mountains', 1932) showed Hitler youths on a summer camp, drilling, wrestling and playing war-games – all against the backdrop of a mountainous setting – finishing with three HJ climbing a dangerous mountain at dawn to conquer it with a Nazi flag. Similarly, Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympiad: A Festival of Beauty (1938) about the 1936 Olympic Games opens with scenes of natural settings including rain soaked oak leaves, birds and squirrels. These segue into a group of men running through the forest; they splash through a pond and, heading into a sauna, wash and massage each other, before going out to swim in the lake. Nowadays, both these films have been labelled as homo-erotic, but the historian needs to remember that Nazism regarded homosexuality as degenerate … as one of the threats to the racial purity of Germany which had to be eliminated. We need to see these films, therefore, rather as a celebration of the ideal Aryan man – IN his Natural setting, and AS the pinnacle of Nature. *** ECO-NAZISMAll this has led some historians to talk about a ‘Green wing’ of the Nazi Party and, in 1997, the British Channel 4 documentary Against Nature declared: "The most notorious environmentalists in history were the German Nazis". Taking the idea further, the historian Anna Bramwell suggested (1989) that the Green movement of today was ideologically connected to – and had developed from – Nazi environmentalism, notably in the way it seeks to root out non-native species and create a ‘pure’ natural environment. Indeed, it is true that German environmentalism had its roots in 1867, when German zoologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term ‘ecology’ as "the interrelationship of organisms and their environments"; he also advocated social Darwinism and racial eugenics, and for a long time the demand for special protections for the environment in Germany lay with the ultra-nationalist Volkisch movement. As one German forestry journal noted in 1939: "Ask the trees, they will teach you how to become a National Socialist". And this meant, of course, as historian Matthew Piper commented (2014), the Nazi environmental laws "seem like a positive thing at first glance, but there is a dark side to them, and they foreshadow the true goals of the Nazis". When Germany conquered Poland, as part of its policy of Lebensraum, the General Plan East proposed to reconstruct the entire Polish landscape along Nazi ideals, replicating the German homelands in the conquered territories … a proposal which involved not only expelling the entire population of 4 million inhabitants, but eliminating all that was non-Germanic about the new homeland, re-building farms and villages; replanting trees, shrubs and hedgerows; and even altering the climate by increasing dew and rain. The implementation of Nazi environmental ideas, moreover, was infused with Nazi antisemitism and predicated on Nazi violence. Part of the motivation of the 1933 Animal Protection Act was to attack Jewish ‘Kosher’ rules. After 1935, Jews were expelled from conservation societies. Jews were removed from Lebensraum land in Poland by death-squads. In 1941, the Nazis took control of the Bialowieza forest in Lithuania and resolved to turn it into a hunting reserve for army officers. No mercy was shown to the Jews, who made up 12% of the population but who violated the ethnic purity of the proposed game farm. Five hundred and fifty Jews were rounded up and shot in the courtyard of a hunting palace operated by Battalion 332 of Von Bock's army division. However, there were many Germans who were not murderous fascists who supported what we would nowadays call the ‘green agenda’. Historian Frank Uekötter (2007) questions whether there was any actual connection between conservationists and Nazism at all. Whilst many conservationists – like most Germans – joined the Nazi Party after 1933, few were Nazis before 1933, and conservation groups – like many other German voluntary organisations – objected strongly to the Gleichschaltung (‘bringing into line’) which had taken over the running of clubs and societies and put them under Nazi leadership in the years 1933-35. A study by the historian Thomas Lekan (2005) on regional planning in the Ruhr found that the RNG actually excluded the members of the previously powerful local Homeland Protection Association from planning decisions. Different people – Nazis – ran German environmentalism after 1935. Besides, as the Marxist writer Louis Proyect commented (2004) "any reasonable person would understand that the gangsters terrorizing Jews and Poles in order to set up a ‘Teutonic’ zoo have nothing in common with today's greens". A surgeon, and a murderer, may share an obsession with total cleanliness … it does not make them friends. *** |

This paintng, by Adolf Hitler, exemplifies the ideal Germanic mountain landscape.

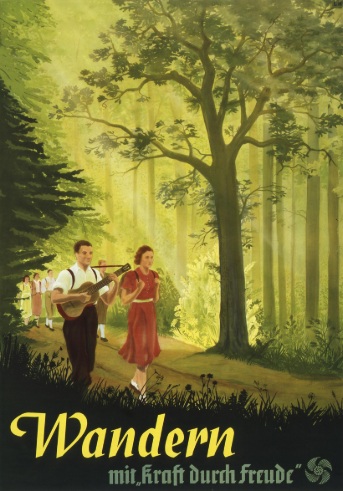

A 1935 KdF poster issued by the German tourism agency: 'Hike, with KdF'.

|

THE LIMITS OF NAZI ENVIRONMENTALISMUekötter has argued that Nazi support for conservation was never very strong. Eric Katz (2014) has argued that it was not about the environment at all, but about ‘domination’ – controlling humanity and Nature to meet Nazi requirements. Either way, the Nazis were only environmentalists when it suited them. A Labour Service – Arbeitsdienst – had been set up in the midst of the Depression in 1931, to create jobs on outdoor projects. On coming to power in 1933 the Nazis immediately increased numbers to more than ¾ million and in 1935 made enlistment compulsory. The organisation was a ploy to train young men for the army (which was still forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles), and the men marched carrying their spades like rifles, but it reclaimed unused land, channelled rivers (most notably, the Ems River) and drained marshland to increase the farmed acreage. By 1941, the Labour Service had created almost 2 million acres of arable land and protected large areas from flooding. An attempt by conservationists to prepare ‘noli-tangere’ (do not touch) maps of ecologically-valuable land was ignored, and Uekötter speculates how great were the consequent losses in biodiversity and aesthetic quality. By comparison, the area of land set aside as protected reserves was tiny. Uekötter also wonders how strictly the 'no compensation' Article 24 was enforced in Germany. He tells the story of a Ruhr farmer who, unable to sell an area of heath for 60,000 Reichsmarks to the local waterworks because it had been declared as a nature reserve, managed instead to negotiate 32,000 Reichsmarks in compensation. There were, of course, no such allowances for the Poles and Jews. At the same time, the Nazis determinedly expanded heavy industry and arms munitions manufacture, with untold damage to the environment. Despite promises, nothing was ever accomplished as regards air quality. Todt generally ignored Seifert’s recommendation for the Autobahns. Goering and other Nazis continued to hunt game, and experimentation on animals continued so widespread that in 1936, the Chamber of Veterinarians in Darmstadt filed a formal complaint against the lack of enforcement of the animal protection laws. Finally the War scuppered most environmental projects. Darré was replaced in 1942 by Herbert Bracke who introduced intensive farming techniques and aggressive timber-felling. The final death-knell for conservation was sounded in March 1943 when, weeks after the defeat of the Sixth Army at Stalingrad, Goering’s Reichsforstamt approved a plan to build a hydro-electric dam in the stunning Wutach Nature Reserve. *** CONCLUSIONSo what was going on? There was an active conservation movement in Germany long before the Nazis, which continued long after the Nazis had gone. For a time, they found themselves with a government that was passing laws in favour of the environment, and it is hardly surprising that the conservationists of the time saw an opportunity to use that government backing to make progress. Equally, for a time, it fitted the Nazis’ beliefs and purposes to talk the language of environmentalism – to use it as a foundation for its ideological beliefs and a justification for its expansionism; to tap into its romance and propaganda-power to bring powerful opinion-blocs on board, not least the environmental and farming lobbies; and to drop when the demands of the War required.

|

RAD conscripts drilling with spades in 1940.

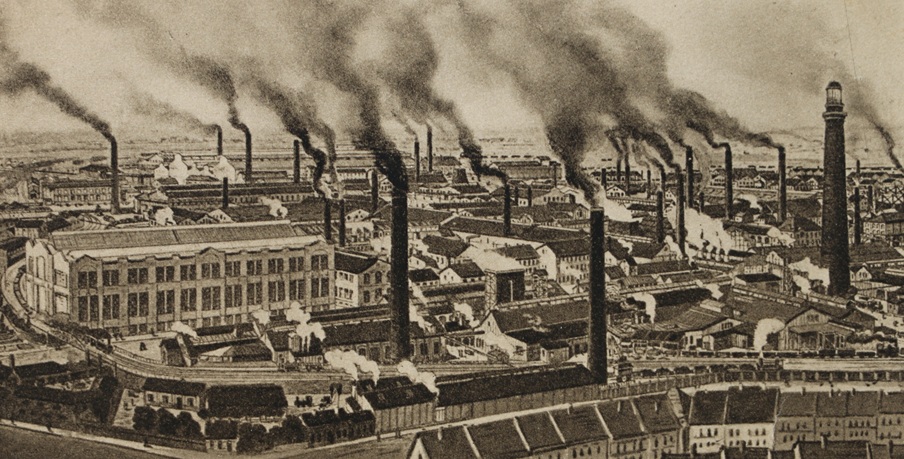

A postcard of the Krupp steelworks in the 1920s-30s.

|

|

| |